ARTIST OF A DIASPORA

Alba Magazine : April 1991

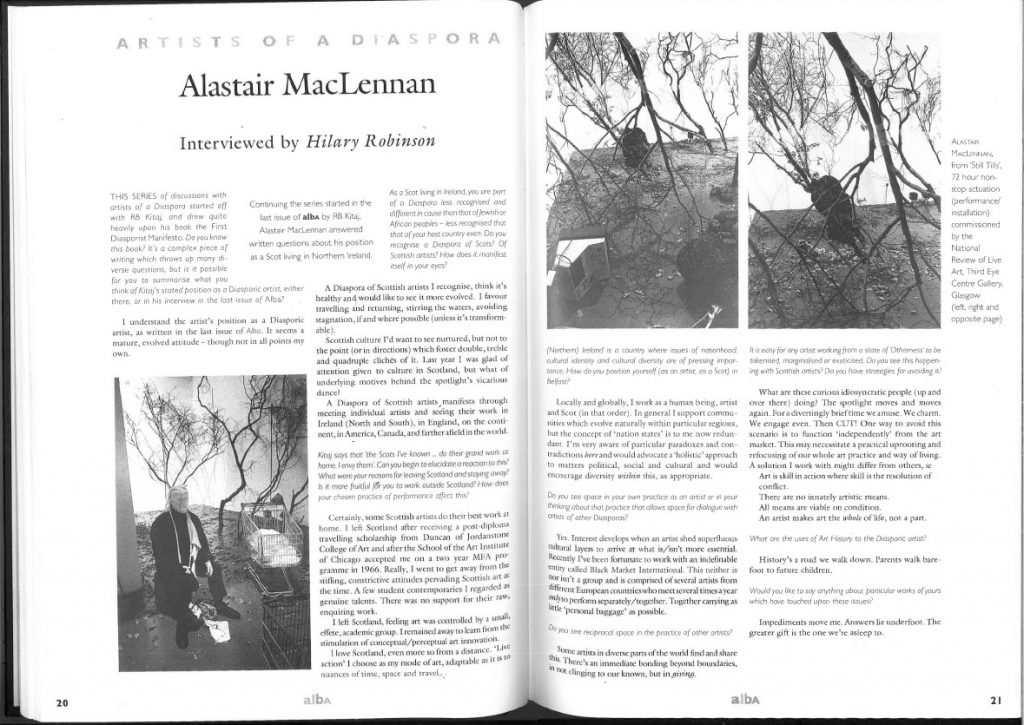

Alastair MacLennan Interviewed by Hilary Robinson

Alba Magazine, April 1991

Continuing the series started in the last issue of Alba by RB Kitaj, Alastair MacLennan answered written questions about his position as a Scot living in Northern Ireland.

H.R.: This series of discussions with artists of a Diaspora started off with RB Kitaj, and drew quite heavily upon his book the First Diasporist Manifesto. Do you know this book? It’s a complex piece of writing which throws up many diverse questions, but is it possible for you to summarise what you think of Kitaj’s stated position as a Diasporic artist, either there, or in his interview in the last issue of Alba?

A. ML.: I understand the artist’s position as a Diasporic artist, as written in the last issue of Alba. It seems a mature, evolved attitude – though not in all points my own.

H.R.: As a Scot living in Ireland, you are part of a Diaspora less recognised and different in cause from that of Jewish or African peoples – less recognised than that of your host country even. Do you recognise a Diaspora of Scots? Of Scottish artists? How does it manifest itself in your eyes?

A.ML.: A Diaspora of Scottish artists I recognise, think it’s healthy, and would like to see it more evolved. I favour travelling and returning, stirring the waters, avoiding stagnation, if and where possible (unless it’s transformable).

Scottish culture I’d want to see nurtured, but not to the point (or in directions) which foster double, treble and quadruple clichés of it. Last year I was glad of attention given to culture in Scotland, but what of underlying motives behind the spotlight’s vicarious dance?

A Diaspora of Scottish artists manifests through meeting individual artists and seeing their work in Ireland (North and South), in England, on the continent, in America, Canada, and farther afield in the world.

H.R.: Kitaj says that ‘the Scots I’ve known … do their grand work at home. I envy them’. Can you begin to elucidate a reaction to this? What were your reasons for leaving Scotland and staying away? Is it more fruitful for you to work outside Scotland? How does your chosen practice of performance affect this?

A. ML.: Certainly, some Scottish artists do their best work at home. I left Scotland after receiving a post-diploma travelling scholarship from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and after the School of the Art Institute of Chicago accepted me on a two-year MFA programme in 1966. Really, I went to get away from the stifling, constrictive attitudes pervading Scottish art at the time. A few student contemporaries I regarded as genuine talents. There was no support for their raw, enquiring work.

I left Scotland, feeling art was controlled by a small, effete, academic group. I remained away, to learn from the stimulation of conceptual/perceptual art innovation.

I love Scotland, even more so from a distance. ‘Live action’ I choose as my mode of art, adaptable as it is to nuances of time, space and travel.

H.R.: (Northern) Ireland is a country where issues of nationhood, cultural identity and cultural diversity are of pressing importance. How do you position yourself (as an artist, as a Scot) in Belfast?

A. ML.: Locally and globally, I work as a human being, artist and Scot (in that order). In general I support communities which evolve naturally within particular regions, but the concept of ‘nation states’ is to me now redundant. I’m very aware of particular paradoxes and contradictions here and would advocate a ‘holistic’ approach to matters political, social and cultural and would encourage diversity within this, as appropriate.

H.R.: Do you see space in your own practice as an artist or in your thinking about that practice that allows space for dialogue with artists of other Diasporas?

A. ML.: Yes. Interest develops when an artist sheds superfluous cultural layers to arrive at what is/isn’t more essential. Recently, I’ve been fortunate to work with an indefinable entity called Black Market International. This neither is nor isn’t a group and is comprised of several artists from different European countries who meet several times a year only to perform separately/together. Together carrying as little ‘personal baggage’ as possible.

H.R.: Do you see reciprocal space in the practice of other artists?

A. ML.: Some artists in diverse parts of the world find and share this. There’s an immediate bonding beyond boundaries, in not clinging to our known, but in giving.

H.R.: It is easy for any artist working from a state of ‘Otherness’ to be tokenised, marginalised or exoticised. Do you see this happening with Scottish artists? Do you have strategies for avoiding it?

A. ML.: What are these curious idiosyncratic people (up and over there) doing? The spotlight moves and moves again. For a divertingly brief time we amuse. We charm. We engage even. Then CUT! One way to avoid this scenario is to function ‘independently’ from the art market. This may necessitate a practical uprooting and refocusing of our whole art practice and way of living. A solution I work with might differ from others, i.e.

Art is skill in action where skill is the resolution of conflict.

There are no innately artistic means.

All means are viable on condition.

An artist makes art the whole of life, not a part.

H.R.: What are the uses of Art History to the Diasporic artist?

A. ML.: History’s a road we walk down. Parents walk bare-foot to future children.

H.R.: Would you like to say anything about particular works of yours, which have touched upon these issues?

A. ML.: Impediments move me. Answers lie underfoot. The greater gift is the one we’re asleep to.